by Juliet Elizabeth Eichorn

Vicus Caprarius

Hard at work in their clunky hard hats, sturdy sensible boots, and dusty khakis, archaeologists might be the last people you’d think would care about fashion. However, when it comes to dating the artifacts they study, fashion can be the most important clue. For example, archaeologists trace fashion trends, like the intricate hairstyles worn by empresses, disseminated and copied across the empire in coins and statues, to determine when a sculpture was created.

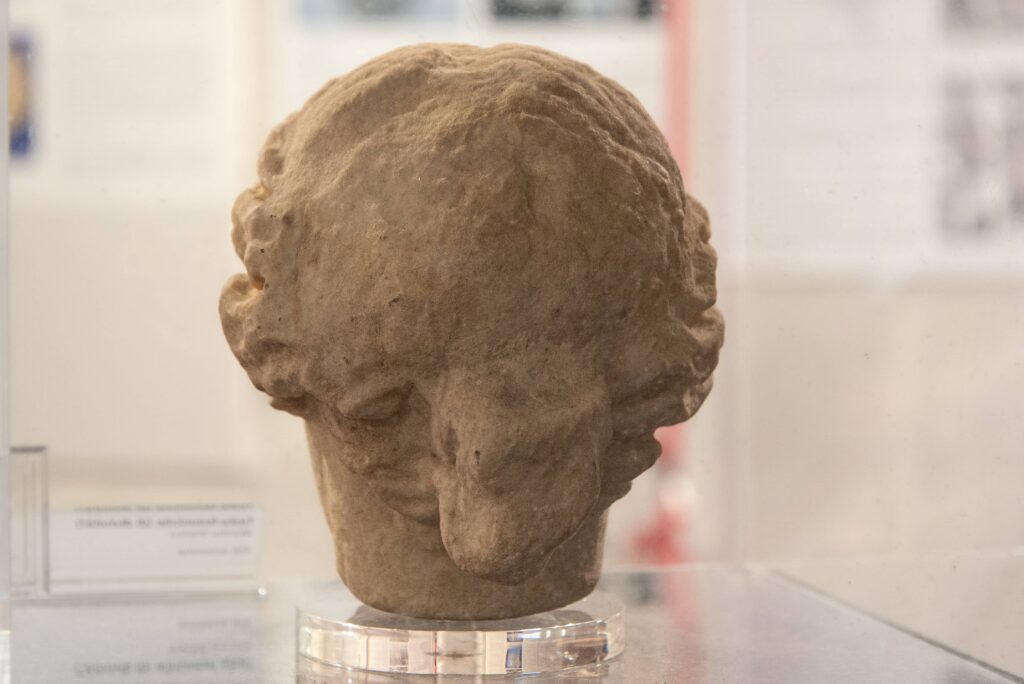

At the archaeological area Vicus Caprarius, a female head is displayed with long wavy hair, tied at the nape of her neck — much like the hairstyle made popular by Faustina II, who married Marcus Aurelius in 145 AD.

Wanting to distinguish herself from her empress mother, who favored plaits that coiled high to create a flat or conical bun on top her head, Faustina wore her hair in a flat bun of plaits, pulled back, and centrally parted and distinctively finished with the plait ends tucked back into the bun’s centre. Hairstyles of one empress were often distinct from her predecessor. The female head on display here can therefore be dated to the Age of the Antonine Dynasty, which began with Antoninus Pius in 138 AD and was followed by his heir Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus until 192 AD. But by the fourth century, this strategy becomes much more difficult because of the Christian custom for women to cover their heads, even at home.

Another marble head on display at Vicus Caprarius is of a young man with a mop of curly hair. Women experimented with wigs and dye but male hairstyles (and hairlines) in Ancient Rome were often down to nature. Perhaps why Augustus’s official portraits portrayed him as a young man until his death aged seventy-six! While dating male hairstyles is difficult, Roman men were known to copy the emperor’s facial hair, who like our marble head, were clean-shaven until Emperor Hadrian in 117 AD. The male representation is believed to date to the late Hadrian Age or the First Antonine Era based on other stylistic details like the cut of the pupils. He could be a well-known face like Alexander Helios, Mithras, Meleager, or Dioscuri.

Likewise on display at Vicus Caprarius is the torso of a woman without head or hands. Here we also have the additional value of her himation. This is a large rectangle of cloth also known as a pallium or mantle, like a cloak but needing one arm raised to keep it in place.

Her tunic underneath would have been more useful to archaeologists as they evolved in length and style. However, respectable Roman women were rarely seen without a mantle. Artwork, moreover, is biased towards formal-wear to which the himation belonged. Drapery of this size and length may have been worn in the late second century.

The folds seemingly continue over her missing hands — a signifier of the deceased. Moreover, her ponytail, still attached to the torso, resembles a style worn by Hadrian’s wife Sabina in the early second century. Sabina wore a loose ponytail tied the ends folded over and tied low. A ribbon ran round and tied at the back of her head. The anachronic ponytail might mean nothing. We are, after all, missing a large portion of the statue and women may keep hairstyles longer than fashionable if it was particularly flattering. Moreover, for those who stood outside time, like deities—or the dead—craftsmen would use “non-temporal” dress instead of the latest fashion.

Here’s a question: what do your clothes and hairstyles say about the 21st century?